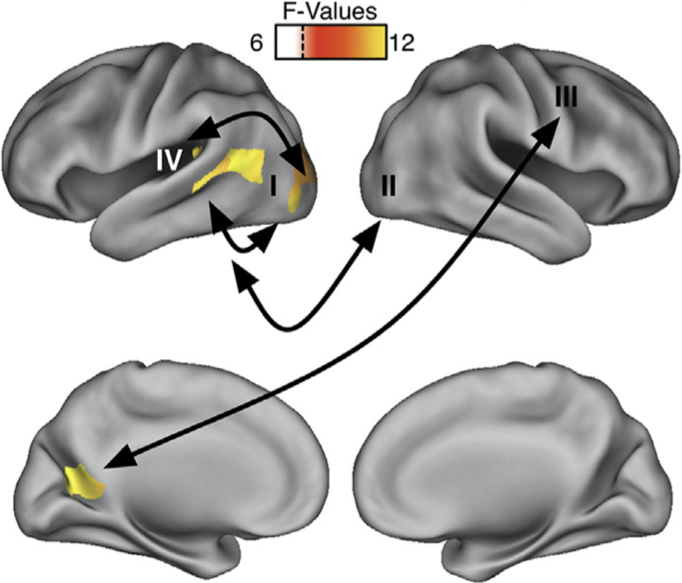

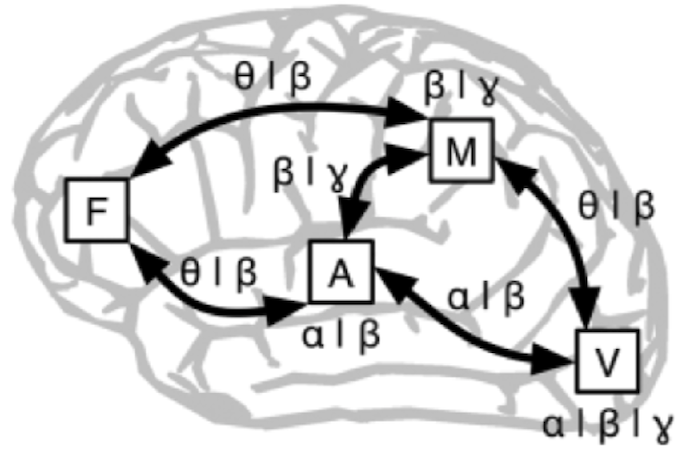

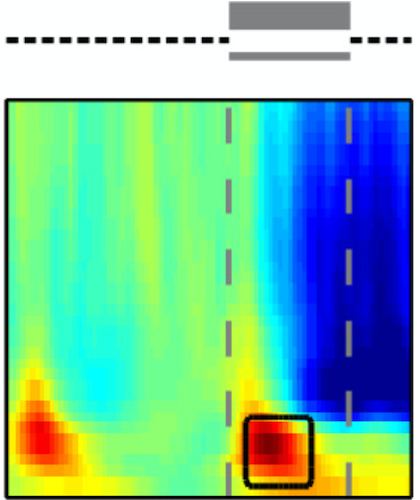

To navigate the world, the brain must assemble diverse environmental stimuli into a coherent picture. This requires fast and flexible communication between brain regions and across timescales (Senkowski & Engel, 2024). Critically, multisensory interactions occur with remarkably short latencies , suggesting they represent a fundamental brain property. These interactions are closely linked to attentional mechanisms , highlighting the intimate relationship between bottom-up multisensory integration and top-down control. Building on this foundation, we have recently begun applying computational modeling to explain how the brain determines which environmental stimuli belong together and integrates this information over time .

Schizophrenia

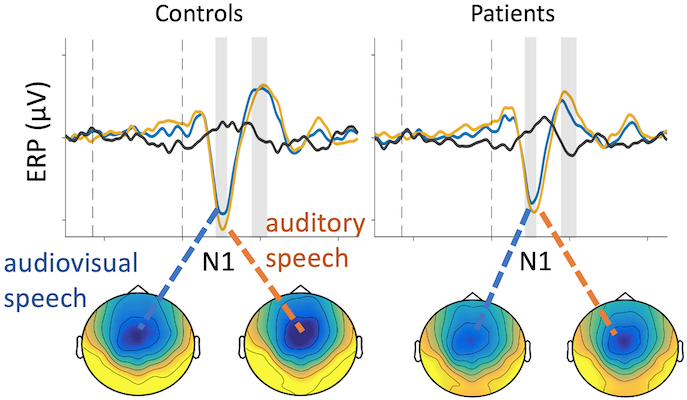

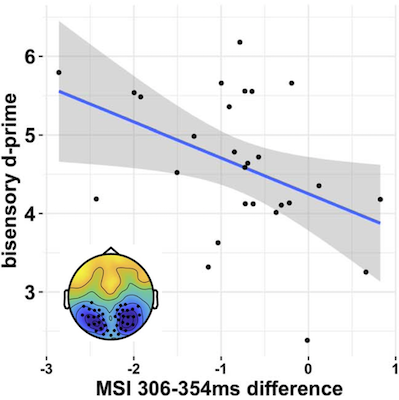

Numerous studies, including our own (Keil et al., 2016; Moran et al., 2019), have suggested that alterations in neural oscillations contribute to the psychopathology of schizophrenia. While the disorder is characterized by florid and debilitating symptoms such as hallucinations and depression, more subtle perceptual distortions and cognitive deficits also emerge. In several studies, we investigated multisensory processing in patients and, surprisingly, found only minor deficits (Balz et al., 2016; Senkowski and Moran, 2022). In contrast, we observed that largely intact multisensory processing can compensate for attentional deficits in schizophrenia (Moran et al., 2021; Moran & Senkowski, 2025).

Pain

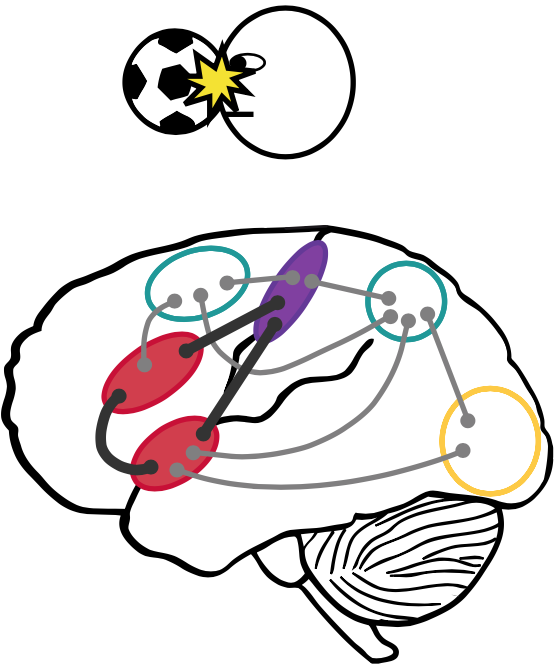

Our studies have primarily examined the processing of acute pain (Senkowski et al., 2011; Pomper et al. 2013). Noxious stimuli in our environment are often accompanied by input from other sensory modalities that can affect the processing of these stimuli and the perception of pain. Stimuli from these other modalities may distract us from pain and reduce its perceived strength. Alternatively, they can enhance the saliency of the painful input, leading to an increased pain experience. A main outomce of our research is that stimuli from other modalities interact with pain, so that they either elevate or diminish the processing and perception of pain (Hofle et al, 2012, 2013). We also hypothesized that chronic pain can distort body representation in the brain (Senkowski et al., 2016)

Other topics

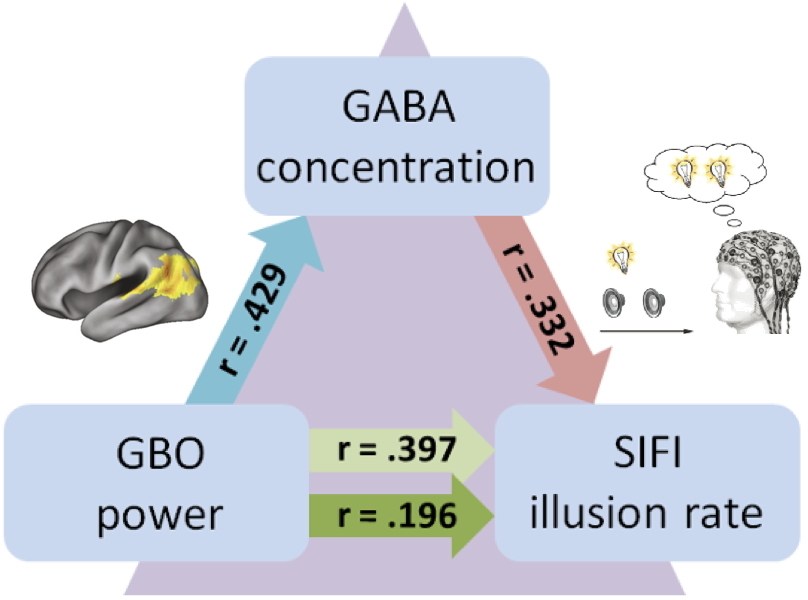

We have conducted smaller projects on other topics, including adult ADHD (Senkowski et al., 2023), generalized anxiety disorder (Senkowski et al., 2003), a collaborative project with the Institute of Sexology and Sexual Medicine (Speer et al., 2020), cochlear implant users (Senkowski et al., 2014), genetic research (Gallinat et al., 2003), functional magnetic resonance spectroscopy (Balz et al, 2018), and health service research (Moran et al., 2021). More recently, we initiated a DFG-funded project on memory processing in post-traumatic stress disorder. This project aims to apply established knowledge of the dynamic neural processes underlying memory to its potential dysfunction in people with PTSD. Memory dysfunction is a prominent feature of PTSD – people’s memories of traumatic experiences are often confused and overlapping, exacerbating the individual's distress. It appears that general working memory and episodic memory performance, even for non-traumatic memories, are impaired in PTSD. We want to test whether these memory deficits can be related to oscillatory features of memory encoding and retrieval, and whether manipulating these signals can actually affect memory performance.